Prepare Your Organisation for the Coronavirus

- KANTRAS

- Mar 3, 2020

- 5 min read

China is the world’s largest exporter of intermediate manufactured products - components destined for use in supply chains across the world. About 20% of global imports of those products came from China in 2015, according to Bloomberg Economics’ calculations based on OECD trade data (see table 1). The longer the coronavirus curtails China’s industrial output, the bigger the risk of disruption to factories elsewhere. For countries in the Asian supply chain, the exposure is bigger. About 40% of all imports of intermediate manufactured products consumed in Cambodia, Vietnam, South Korea and Japan came from China in 2015.

Table 1: Bloomberg publication on how the Coronavirus effects the worldwide supply chain

In the past weeks the media reported that the Coronavirus impacts the following industries:

Aviation

Car industry

Retail

Tourism

Medical technology for hospitals

Even so these industries where the first to be affected by the Coronavirus a KANTRAS’ survey under 113 European companies and KANTRAS’ customers shows a different and more alarming picture. 65% of the companies responded that their supply chain will be affected by the lower production capacities in China and they will see the effects in April/May this year. 52% still have sufficient stock to facilitate the March 2020 supply for the forecasted sales.

In the last weeks most of KANTRAS’ strategic project where put on hold and our capacities where mainly shifted to improve or rescue our customer’s supply chain mainly in Retail, the Consumer Goods Industry or Producing Companies. SME are struggling the most due to single sourcing, small stock amounts or because they are short on cash.

What You Can Do Now

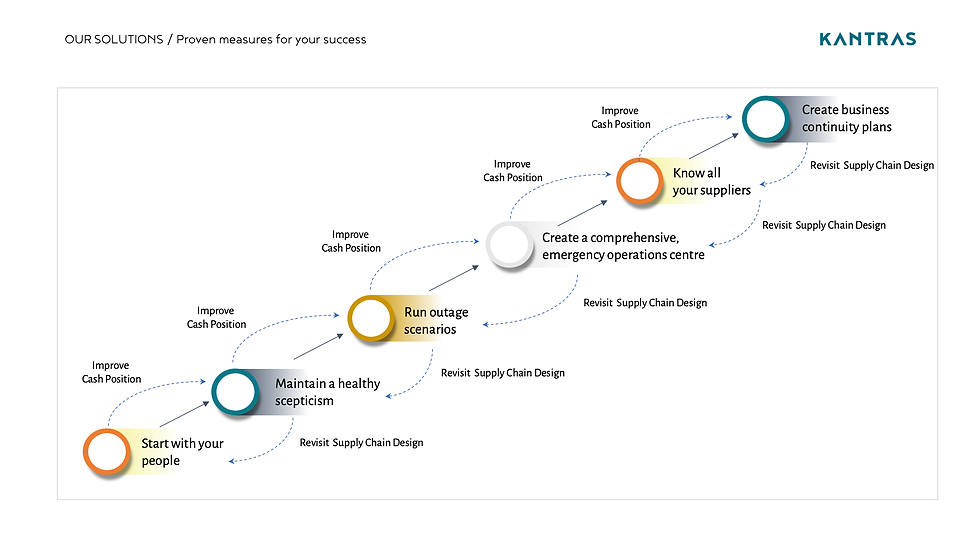

Let’s first look at some actions that can be taken to mitigate the impacts of the crisis on supply chains (see table 2).

Start with your people. The welfare of employees is paramount, and obviously people are a critical resource.

A backup plan is needed for people too. The plan may include contingencies for more automation, remote-working arrangements, or other flexible human resourcing in response to personnel constraints. Home Office only works for approx. 10% of a company’s staff complement.

Table 2: Improve Cash and the Supply Chain Design at the same time

Maintain a healthy skepticism. Accurate information is a rare commodity in the early stages of emerging disasters, especially when governments are incentivized to keep the population and business community calm to avoid panic. Impact reports tend to be somewhat rose-tinted. However, local people can be a valuable and more reliable source of information, so try to maintain local contacts.

Run outage scenarios to assess the possibility of unforeseen impacts. Expect the unexpected, especially when core suppliers are in the front line of disruptions. In the case of the coronavirus crisis, China’s influence is so wide-ranging that there will almost inevitably be unexpected consequences. Inventory levels are not high enough to cover short-term material outages, so expect cause widespread runs on common core components and materials.

Create a comprehensive, emergency operations center. Most organisations today have some semblance of an emergency operations center (EOC), but in our studies we’ve observed that these EOCs tend to exist only at the corporate or business unit level. That’s not good enough - a deeper, more detailed EOC structure and process is necessary. EOCs should exist at the plant level, with predetermined action plans for communication and coordination, designated roles for functional representatives, protocols for communications and decision making, and emergency action plans that involve customers and suppliers.

The coronavirus story will undoubtedly add to our knowledge about dealing with large-scale supply chain disruptions. Even at this relatively early stage, we can draw important lessons about managing crises of this nature that should be applied down the road.

Know all your suppliers. Map your upstream suppliers several tiers back. Companies that fail to do this are less able to respond or estimate likely impacts when a crisis erupts. Similarly, develop relationships in advance with key resources - it’s too late after the disruption has erupted.

Many supply chains have dependencies that put firms at risk. An example is when an enterprise is dependent on a supplier that has a single facility with a large share of the global market.

Create business continuity plans. These plans should pinpoint contingencies in critical areas and include backup plans for transportation, communications, supply, and cash flow. Involve your suppliers and customers in developing these plans.

Revisit Your Supply Chain’s Design

Many development steps have to be taken before a supply chain functions smoothly, efficiently and stably. In many cases, however, the prelude to a reorganisation is a crisis situation like the one most of our European customers are facing with the Corona virus right now: the parts are not there, production is at a standstill, delivery dates cannot be met, customers are shifting to other brands or suppliers, etc..

Meetings to prioritise orders take place, rescheduling is the order of the day, parts hunters are deployed, etc. As a result, the majority of the organisation is tied up in ad hoc management and, in order to get out of this chaos quickly, short-term measures should bring about the solution.

Anyone who has ever experienced such a situation knows that short-term measures designed to optimise a supply chain are usually not sufficient to overcome the crisis.

This has several reasons:

The problems that arise cannot be easily isolated; they usually arise in the interaction of the functional areas along the supply chain. Thus, the causes are also systemic in nature and the improvement of the situation requires further development of the overall system.

If a supply chain develops over years in a direction of susceptibility to faults and errors, it cannot be expected that within 4 weeks the errors of the last years can be eliminated. Often, an improvement of the supply chain is also associated with organisational developments, which take half a year to a year.

The more errors there are in the system, the more serious the consequences: incorrect storage allocation, missing parts, priorities for all orders, etc. start a downward spiral that progresses inexorably. Short-term measures are quickly overtaken by new crisis situations, the frustration in the team grows daily.

Which way now leads out of the chaos? Our experience from many start-up projects and crisis situations with customers in various industries has shown that it is necessary to consistently pursue 2 strategies in parallel:

The strategy of stabilisation and the strategy of optimisation

The strategy of stabilisation focuses purely on life-sustaining measures. The aim is to calm production and logistics to such an extent that no further errors are added in terms of wrong parts, incorrect storage, missing parts etc. in order to get out of chaos. Permanent rescheduling and priority lists must be abolished first. With a calmer production, the output also increases and the first milestone to break the vicious circle is reached. This requires higher inventories and often additional management capacity so that one part can concentrate on exception handling and the other on the standard. It is a misconception to try to do this at minimal cost. The necessary investment pays off quickly when the management can resume normal tasks and does not remain in a state of emergency.

Supply Chain Optimisation is a first step in a root cause analysis

Parallel to this, however, the optimisation phase must be initiated. In the stabilisation phase, the causes are usually not combated. The errors are only covered up by higher stocks and more personnel, so that you can get back 'on track'. The first step in the optimisation phase is to trigger the root cause analysis, and to do this you have to orient yourself to the process.

The success of such a crisis management lies in the parallelisation of the two approaches: for stabilisation you have to put money in your hands to achieve a quick calming down. This requires additional capacities at both the management, operational levels and cash management. As a rule, you also buy reassurance through stocks. Optimisation usually takes 6 to 12 months and must get to the root of the problem. It goes hand in hand with a redesign of the process and organisational structure and requires an alignment of all functional areas along the supply chain.

Comments